‘THE SACRIFICIAL ELEMENTS’

The Greek Tragedy of Our Dying Olive Trees

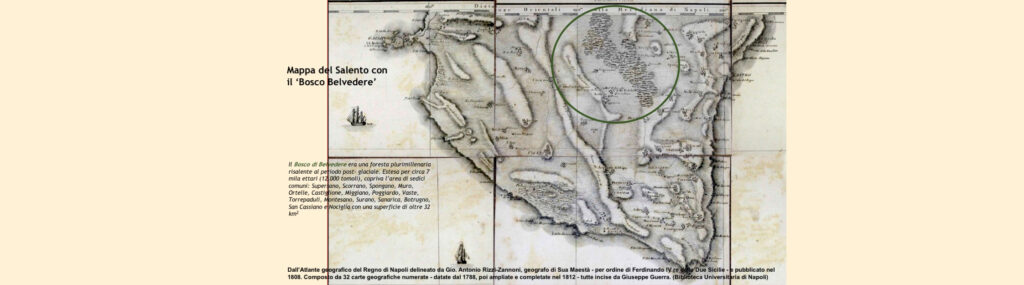

My dear friends in Turkey, I am writing to you from Salento to recount a dark tale of how the trees in our area have been infected by a kind of plague. We are ‘Mediterranean cousins’ – Salento and Istanbul not only share the same latitude, but also the same age-old tradition of growing olives.

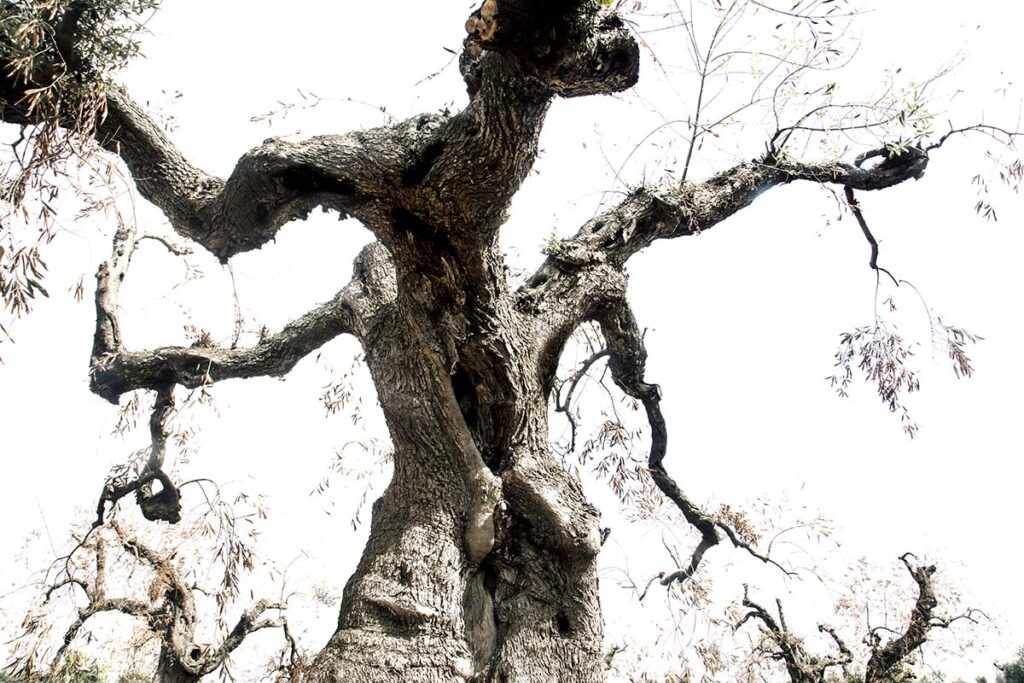

So, thanks to our shared customs, you will easily be able to imagine this extreme tip of southern Puglia as a vast green expanse of millions of trees, approximately 11 million, dedicated to the goddess Minerva. Many of these trees are patriarchs that are over a hundred years old, some over a thousand, and whose hollow trunks could still cradle Odysseus’ bed, as narrated by Homer.

A plague has struck, just like in a medieval epidemic.

I would like you to try and imagine you are flying above this calcareous peninsula surrounded by the blue sea, and, at the center, a mantle of green with enormous patches of dull brown, the bronze color of withered trees that dot our landscape.

A mantle that ominously dominates our countryside. Just like the lesions that suddenly appear on the skin of a person affected by a vile disease, the Salento Peninsula expresses all its suffering, and it is the olive trees that are the sacrificial elements as they are withering by the thousands and our landscape has been completely altered.

You are also a people of seafarers and will know that zinc blocks are applied to the hulls of ships to save the hull from the galvanic currents, unbeknownst to the sailor, that slowly erode the metallic components of the boat, undermining the survival of the whole ship.

These anodes are called ‘the sacrificial elements’, unseen because they are underneath the ship, and are replaced with a kind of gratitude when they are worn down. Continuing with the metaphor, just as you can see a disease infecting a town where, entirely at random, some people contract the illness, and others do not, and the superstition that has accompanied us since time immemorial, the first thought of those who survive is that within their own family and within their own town, some gave their lives for others.

The olive trees are the sacrificial anodes in Salento, whose land has been diseased for some time, but whose fruit also nourish the people who live here. I cannot keep this from you, in this dark tale, the fact that southern Puglia has the highest mortality rates due to cancer resulting from environmental causes despite not having major industries, like the ones in northern Italy.

The ‘olive tree plague’ and the increasingly crowded oncology wards are clear symptoms of the same disease, caused by the iniquitous abuse of the environment. These huge brown patches that have become part of our landscape as well as a source of bewilderment for hundreds of helpless farmers when faced with their withered trees, are the most obvious and the most ‘spectacular’ symptom – just like the explosion of malevolent sores on a sick person’s skin – of a poisoned land.

My view might seem apocalyptic to you, but I assure that all of us here realize we are witnessing an epochal change (seismic shift).

A weak body cannot defend itself from the plague

This dark tale begins shortly after the year 2000 when withered branches suddenly appear amidst the dense foliage of a few olive trees. The farmers as well as the botanists believe this phenomenon is caused by several factors, for example, by a disease known as OQDS (olive quick decline syndrome), which is when plant-sucking parasites spread bacteria that restrict the flow of sap within the tree and so choke its extremities. At first, the disease appears as patches, just one withered branch, and then, little by little, it spreads to all the foliage.

One of these parasites is Zeuzera pyrina, or the leopard moth, and at least four fungi (lignicolous fungi), which have always infected olive trees. Thus, growers are used to coping with these issues by employing traditional methods such as slupatura, a technique where the farmer cuts deeply into the diseased part of the tree trunk. Today, very few people use this age-old technique where the hollow part of the trunk is cleaned out, removing the decayed wood, which has been infected by fungi. Then it is disinfected with a copper-based timber preservative and is often also scorched. Not to mention that olive trees are among the most durable and known to heal on their own if well taken care of.

Just as farmers are no longer carrying out slupatura, other traditional techniques for growing olive trees have been neglected in Salento over the last 30/40 years. There are many abandoned fields and the traditional treatments have been replaced by an abnormal use of pesticides. According to an ISTAT (the Italian National Institute of Statistics) estimate, Puglia is the biggest consumer of pesticides and chemical agents, and Salento is in first place within the region. The senseless use of chemical products has not only depleted the soil and caused subsequent loss of biodiversity, but it has also leached into the groundwater, poisoning our water resources, already almost depleted.

The process of desertification has already taken its toll in Salento. Due to climate change, desertification has become a global issue, but several researchers raised the alarm at the beginning of the 2000s.

However, as with Cassandra’s prophecies, nobody heeded their warning: “there is no doubt that there will be the complete desertification of Puglia, starting with Salento, and the effects will be felt within a decade.” They reported the salinization of the groundwater, also due to numerous illegal deep wells that have altered the delicate system between the aquifers of surface water and those of salt water, which are deeper. And since this is a dark tale, I will add that since the 1980s, tons of extremely dangerous industrial toxic waste have been illegally buried in the Salento countryside, poisoning the land beyond repair because it is impossible to reclaim the contaminated soil.

If, once upon a time, OQDS infected trees without killing the ones that were basically healthy and well-cared for, in recent years, these pathogens have found ‘fertile terrain’ to proliferate in trees that are already suffering – either their roots can no longer find the groundwater that used to run just a few meters from the surface, or the water they find is contaminated or saline. I have digressed, my dear friends, this story of the last 30/40 years, however, is necessary to better understand the present.

In just over 10 years, these isolated cases of branches suddenly withering have become a real epidemic, and entire areas of Salento have turned bronze/brown.

The enemy is real, has a name and must be unmasked/pilloried

A slaughter! What do they know in Strasbourg about the environmental situation in Salento? The EU Commissioners do not know what the politicians in Puglia know. On the one hand, soil that has been polluted for years and years by pesticides and groundwater that has been depleted, salinized, and contaminated by chemicals. On the other hand, many small organic farms and holdings who employ traditional methods to combat the infection, plant ancient seeds and refuse to use pesticides. Now, according to the EU directives, these organic farmers must use pesticides and eradicate their trees.

Moreover, there is no scientific evidence that X. fastidiosa is the only cause of decay. All the analyses carried out on thousands of the infected trees that have withered reveal that the bacterium is present in slightly under 2% of the trees analyzed. Nevertheless, X. fastidiosa becomes synonymous with the death of olive trees and justifies the total upheaval of the Salentine landscape.

A schism immediately develops. The European Union, the Italian government, the Puglia government, and the associations like Coldiretti, whose aim is to protect farmers agree to adopt the atrocious solution: eradicate trees and poison Salento with pesticides.

On the other side, a popular uprising grows in Salento and “Keep off the olive trees” is their cry. The movement is made up of farmers, environmental groups, artists, and civil society who cannot imagine their land without olive groves but instead battered by pesticides, and they manage to make themselves heard in Strasbourg. Conferences and awareness campaigns are organized, and important chemists and botanists are called in order to discuss the decay of the olive trees as part of the more general issue of environmental pollution. The media campaign, however, is intense and even the international media embraces the theory that the X. fastidiosa bacterium is the sole culprit of the decay of the olive trees. Hundreds of olive trees are uprooted, but not all of the ones that have been dictated by the emergency plan, thanks also to local judges who do not believe in the X. fastidiosa theory, and so time passes in a sort of waiting game.

Many have given up over the years or kept silent – the silence of mourning – and accepted the dramatic uprooting of trees as fated. There are many, however, who have resisted, especially the organic farmers who now take sceptics into their fields so they can see for themselves that olive trees that were given up for dead are slowly recovering, thanks to the traditional treatments that had never been abandoned. They are the same people who, together with a few brave journalists, have been exposing the economic speculation that is lurking behind the theory of the X. fastidiosa bacterium killer.

Uprooting olive trees has met with resistance on a local level, however, at the same time, Italy is being heavily fined by the EU for not implementing the emergency measures in the allotted time. So, as this waiting game continues, the agri-economic plan the Puglia government has in mind to revive the olive oil industry has become clear.

Salento, which has always been one of the major olive oil producers worldwide, has undergone a drastic drop in production – a reduction of nearly 60%. Many olive press owners have been dismantling their machinery so they can sell it to producers in the Mediterranean countries, whose business has been growing over the last decade. “The oil industry, which has fallen due to Xyella, needs to be revived”, politicians say, “Let’s get rid of the old olive trees, abandon the traditional methods and switch to a super-intensive cultivation, using new resistant species”.

Who stands to gain from Xyella?

As I have told you, there is no scientific evidence that the only cause of the decay of the olive trees derives from the Xyella bacterium. Indeed, this bacterium is only one of the pathogens of OQDS (olive quick decline syndrome), it is only one of the contributory causes, like the leopard moth and the fungi, which together make up a kind of lethal cocktail that attacks the sap transport in plants. Repeating and spreading information, however, that the sole culprit is the ‘famous quarantine bacterium’, creates confusion and hinders discussion about the atrocious use of pesticides over recent decades. As a result, there is little talk about the fact that Salento shares the same tragic fate as Africa – they are both the toxic waste dumps of the industries of the Western World. In addition, silence surrounds the fact that the desertification of Salento is equal to the levels in areas in the Sahara, consequently, the content of organic substances in the soil is nearly absent.

To pursue the theory of the ‘X. fastidiosa bacterium killer’, which is known worldwide to be impossible to stop, means pursuing the eradication of olive trees on a massive scale as the only viable means of preventing the spread of the bacterium. In short, getting rid of all the olive trees in Salento, even the age-old patriarchs, to make way for two species that are not indigenous, the Leccino and especially the Favolosa Fs17 (patented by the CNR in Perugia, and quite costly since royalties must be paid on every plant).

The introduction of these two olive species, both which seem to be resistant to Xyella, and not immune – ‘resistant’ only means that they may get infected later, there is no scientific certainty that they will not get infected. Such a solution signifies opening the way to a super-intensive type of agriculture since these trees are small shrubs that can be planted closely together but require a great deal of water as well as chemical agents to protect them from disease. They are also short lived and must be replaced after at most 10-15 years as they are no longer productive. Try and imagine how the landscape will be changed and how much water will be needed: growing indigenous olive trees, for example, Ogliarola and Cellino, which are the most common, there are approximately 80 trees on a hectare of land using traditional methods, whereas the same hectare would host 500 Leccino and 1600 Favolosa Fs17 using the super intensive method.

Another ‘perk’ due to Xyella is the allocation of substantial funding from the European Union as well as from the Italian government. To date, 300 million euros have been allocated, and these funds are aimed at promoting super intensive agriculture by planting the two non-native species of olive trees on a massive scale. This money will go to producers who have at least 5 hectares, and not to small oil producers. They have promised to pay €200 – €300 for each uprooted tree, so the small producers will pocket very little money, and then sell their land which has become barren to big landowners or to international corporations. The latter, possessing more than 5 hectares, will be entitled to economic incentives for the extremely expensive as well as intensive cultivation of the new species of olive trees.

Here is the picture: a Salento where its age-old culture is uprooted, and its Homeric landscape and its olive trees that are resistant to frequent droughts like ancient prehistoric animals are eradicated to make way for the super intensive agribusiness that needs water in a land where water is scarce. Literally, land-grabbing – a term which accurately describes this agribusiness transaction. This has already occurred in Almeria in southern Spain as well as in other economically challenged areas of the world, and often it is the poor who are the sacrificial anodes of the world. Now, I think that you can also hear, in the background of this dark tale, the lament of the chorus of the Greek tragedies.

Ada Martella

September 2019

I could not have told this tale without the support of the studies, the research, and the investigations of many experts. I would like to cite the people that are most dear to me – who may themselves be considered ‘sacrificial anodes’, for having the courage and the ability to explain a complex truth. A truth that is not accepted by the political and financial system, and that is why they have been subjected to threats and

Luigi Russo, journalist and author of many investigative reports on the relationship between Xylella and the agri-Mafia. Luigi died a few months after this report was published, but not before bitterly sharing what it is narrated here.

Marilù Mastrogiovanni, journalist and author of the book ‘Xylella Report’, edition Il Tacco d’Italia 2015.

Ivano Gioffreda, farmer and the heart and soul of ‘Il Popolo degli Ulivi’ (the People of the Olive Trees).

Giorgio Doveri, chemist and musician.

Michele Carducci, professor of Comparative Constitutional Law as well as of Climate Change Law at the University of Lecce (Università del Salento). An expert in law and climate justice, his studies on the ecological/environmental vision of the law have been a source of great inspiration.

Enza Pagliara, singer and friend of ‘Il Popolo degli Ulivi’, she is one of the artists and singers who has supported the farmers’ and ecologists’ movement against the eradication of the olive trees.

This report was commissioned by the Turkish magazine ‘Sabah Ülkesi’ and published in issue n.61 in 2019 (Istanbul). The report was accompanied by photos taken by Bruna Rotunno and Fabian Albertini, photos that are part of the De Finibus Terrae

Photography Project.