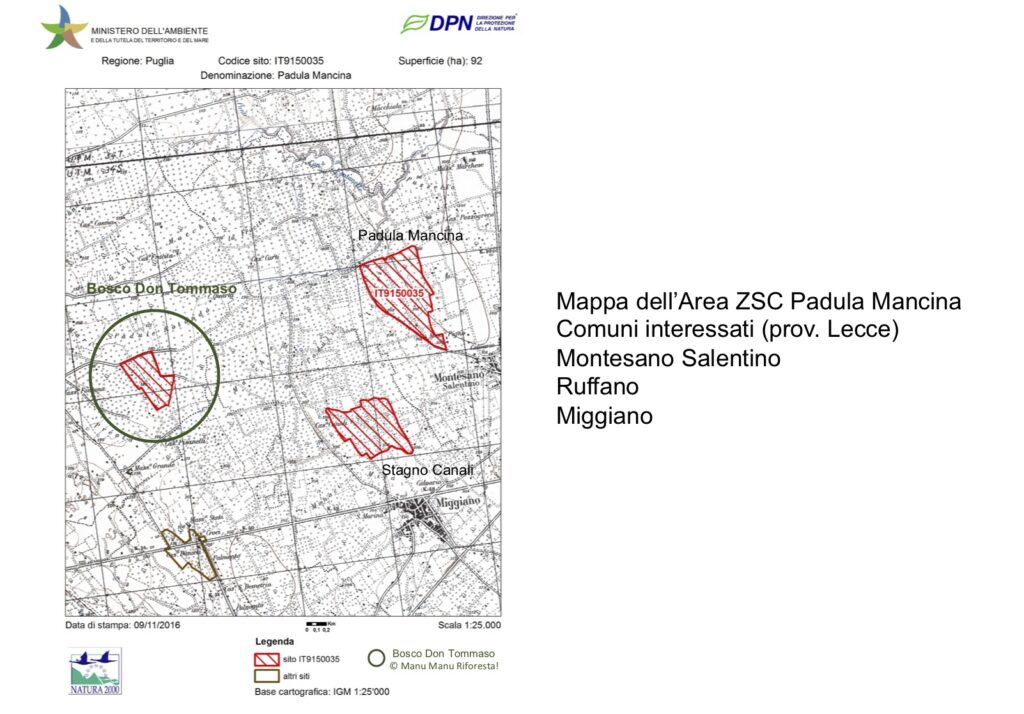

The agricultural area of the Salento known as the Paduli is bounded by an almost ellipsoidal line of c.40km that extends from Scorrano to Miggiano.

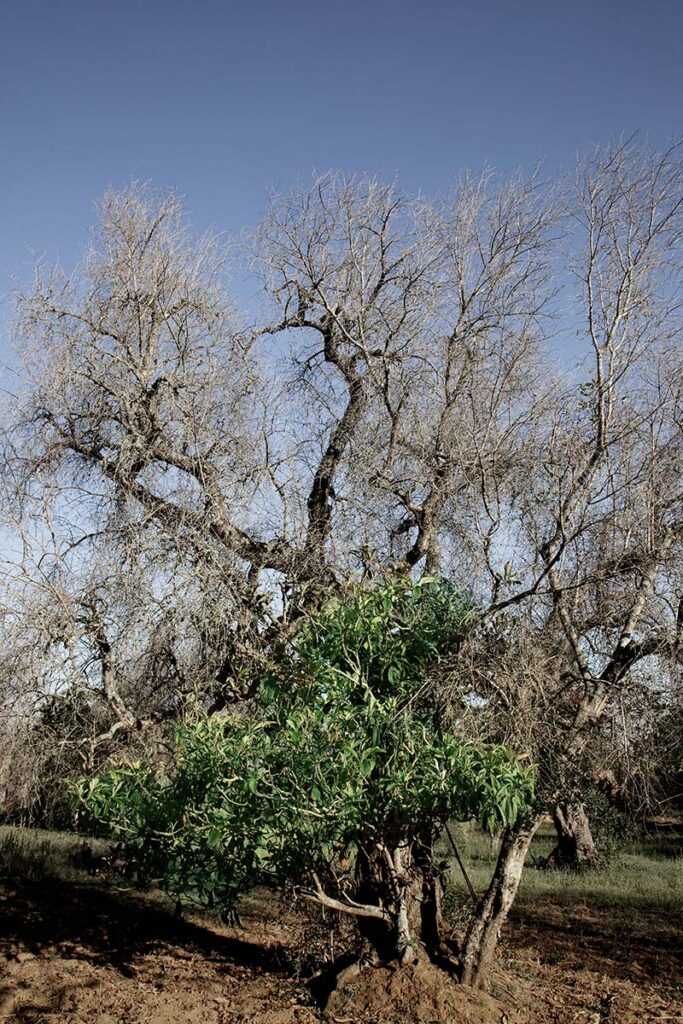

Until about 500 years ago it was known as Bosco de Belvedere, a forest dating back several millennia to the post-glacial period. Extending over about 7,000 hectares (c.17,000 acres) in the territory of 16 different municipalities in the southern heart of the Salento, it had a surface area of more than 32 square kilometres. It was an area rich in ecosystems from woodland to garrigue, marshes to ponds and to Mediterranean macchia. Today the water coming from the hills is still transported to this area through a network of canals, often flanked by rich vegetation. The first historic documents that attest to the existence date back to 1476; in fact, the Bosco Belvedere is listed in the inventory of the fiefdom of Supersano drawn up for the Gallone Princes of Tricase to whom it belonged for almost 300 years. Previously it was the property of the Castriota, barons of Parabita. In 1851 the order to divide the woodlands between the communes that exercised civic use there was executed. And after a long-running contention with the powerful noble families that held the wood, the area was assigned to the various municipalities. With this act of division was signed the inexorable destruction of the forest, and in a few decades what little had survived fires and illicit wood cutting was rapidly eliminated to make way for the emerging tree culture: the olive.

Numerous historic and archaeological researchers attest that this great forest was for millennia a fount of sustainment for the people who lived next to it, as is evidenced by the discovery of a VIth-VIIth century AD village in the locality of Scorpo, near Supersano.

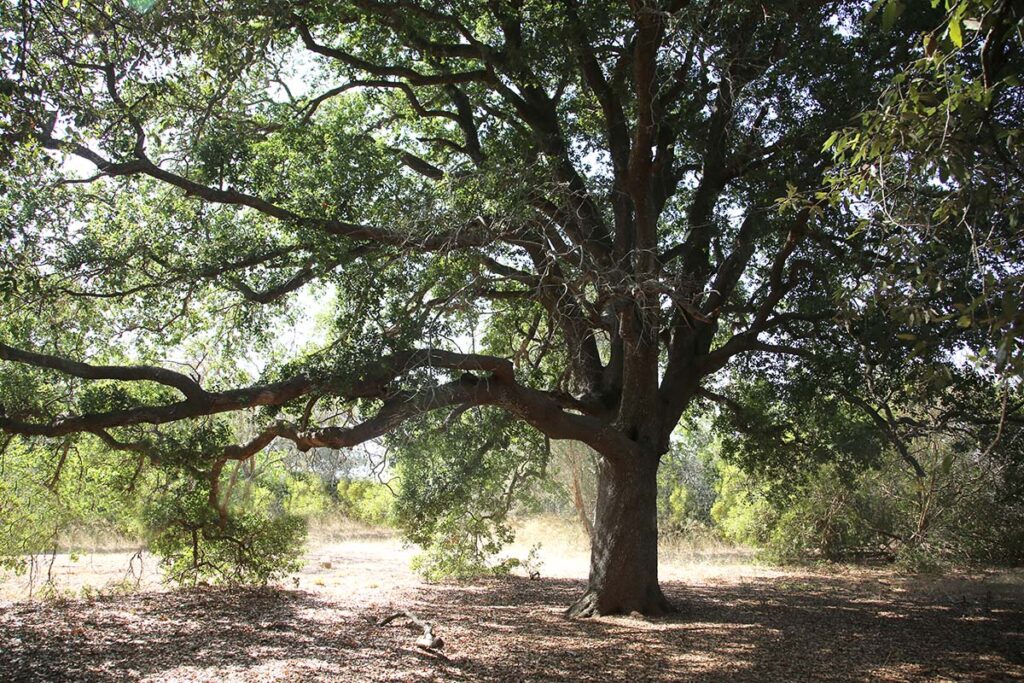

In the dense wood prospered, uncultivated, plants such as “the wild plum, the strawberry tree, apple, pear, barbary fig, wild vine, rowan and medlar”. Foxes, hares, rabbits, badgers, porcupines, hedgehogs, weasels, martens and polecats found refuge there, and there was no shortage of “voracious wolves and wild boar, of which the last was killed in 1864, the year in which the wood was reduced by almost half,” as the 19th century scientist Raffaele Marti recounted. This immense forest of oaks, amongst which the Italian oak, the downy oak and the virgilian, also included elms, holm oaks, chestnut trees, ash and hornbeam, and plants and flowers of the undergrowth and Mediterranean scrub such as laurel, strawberry tree, lentisk, myrtle, viburnum, holly, rosemary, mulberry, roses of San Giovanni and with no shortage of apples, pears, rowanberries, medlars, wild grapes. The forest guaranteed substantial income for the ‘civic uses’ granted by the princes through the payment of dues, such as concessions for fishing, collecting fruits and wood, reeds and canes, the cultivation of linen and hemp, raising sheep and pigs, together with the production of charcoal, hay, acorns for pigs, the use of the myrtle and other medicinal plants, as well as the right to hunt birds.

From the beginning of the 18th Century to the end of the 19th this ancient and precious nature reserve disappeared bit by bit, shrinking almost to the point of extinction to give way to cultivation to the point at which Arditi in 1879 wrote, “It was this wood that was perhaps the most vast and varied for its types of trees in the Province, but now there are no more shrubs and copses if not a few “moggia” to the northwest towards Supersano; all the rest is reduced to galloping scrubland or to land cultivated with figs, vines and cereals.” Today there remain few islands of that treasure trove of biodiversity and naturalness. In 1877 Cosimo De Giorgi wrote, “It is not without the greatest pain that I observe year after year felled to the ground those majestic oaks that have stood up for so many centuries to the damage of weather, of the atmosphere, of men and animals. The scythes and levelling axes of the woodsmen leave their mark too, on this inexorable road to destruction […]”.

Now in the Province of Lecce barely 1.3% of agricultural land is wooded, placing the Province near the bottom of the league table relating to woodland areas in Italy.

Bibliography

Raffaele Marti, L’estremo Salento, Lecce 1931, pp. 21-23.

Donatella Lala De Giorgi, L’archivio del Principi Gallone Ed. Dell’Iride Tricase 2001

Giacomo Arditi, Corografia fisica e storica della Provincia di Terra d’Otranto, rist. an. Lecce 1994, p. 65. L’Arditi aveva conosciuto nelle sue varietà e bellezza il Bosco perché, nel 1851, aveva ricevuto l’incarico di tracciarne la mappa e stabilire la divisione in quote tra le parti interessate.

Michele Mainardi, Il Bosco di Belvedere, «Lu Lampiune», a. V, n. 3, 1989, p. 108

Aldo De Bernart, Torrepaduli scomparsa in A. De Bernart-M. Cazzato-E. Inguscio, Nelle Terre di Maria d’Enghien, Galatina 1995.

Paul Arthur, Girolamo Fiorentino, Marco Leo Imperiale, L’insediamento in Loc. Scorpo_Supersano, Archeologia Medievale XXXV, 2008, pp. 365-380 (vedi sezione Approfondimenti).

Roberto Gennaio, Biagio De Santis, Piero Medagli, Alberi Monumentali del Salento, Congedo Editore, Lavello 2000.